Latinitas of INA: from Providentiae Munus to Novus Decor

06 November 2017

Ina Assitalia Historical Archive

It is widely known that the custom of decorating buildings with inscriptions in both Latin and Italian was commonplace in public and private institutions during the first several decades of the 1900s. That the Fascist regime used this particular custom as a means of propaganda is also a well-known fact. These affirmations can be further confirmed in the documents found in the INA-Assitalia Historical Archive.

In fact, INA, the Istituto Nazionale delle Assicurazioni (National Insurance Institute), a public body founded by Giolitti in 1912 to manage the life insurance business in a regime of monopoly, was not immune to this trend, as is evident in the two inscriptions engraved into the facades of the two prestigious institute buildings in central Rome, the Palazzo on Via Sallustiana designed by engineer Guido Giovannozzi and the Palazzo on Piazza Sant’Andrea della Valle designed by architect Arnaldo Foschini.

Through reading these brief inscriptions it is also possible to track the transformation of INA from the Giolitti institution conceived by the Minister of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce, Francesco Saverio Nitti, with the specific objective of spreading the “Spirit of Security” to all social classes, even the most humble, to the Mussolini-inspired institute defined by the Duce as “a financial force of the Fascist State”, becoming an effective tool of the architectural renaissance promoted by the Fascist regime.

In 1927 the top management of INA, in the presence of religious and civil authorities, and of Benito Mussolini, head of the government, inaugurated the new Head Office on Via Sallustiana, where the inscription above the three arches of the monumental entrance once bore (today the words are almost invisible due to pollution and smog) the grand Latin inscription:

Providentiae munus res publica sibi vindicat

(The State claims the duty of Security, transl.)

which still fully acknowledged, even though in the peak of the Fascist period in the country – the infamous Fascist Racial Laws had been enforced for a year –, a new social commitment, the Providentiae munus, which the Italian state assumed through the creation of the Institute in 1912. The author, INA Official Adolfo De Gregorio, wished to emphasise this national and governmental commitment in his sentence which, “being himself in possession of a modest knowledge of Latin”, for the sake of clarity he had also subjected to “highly qualified Latin experts”.

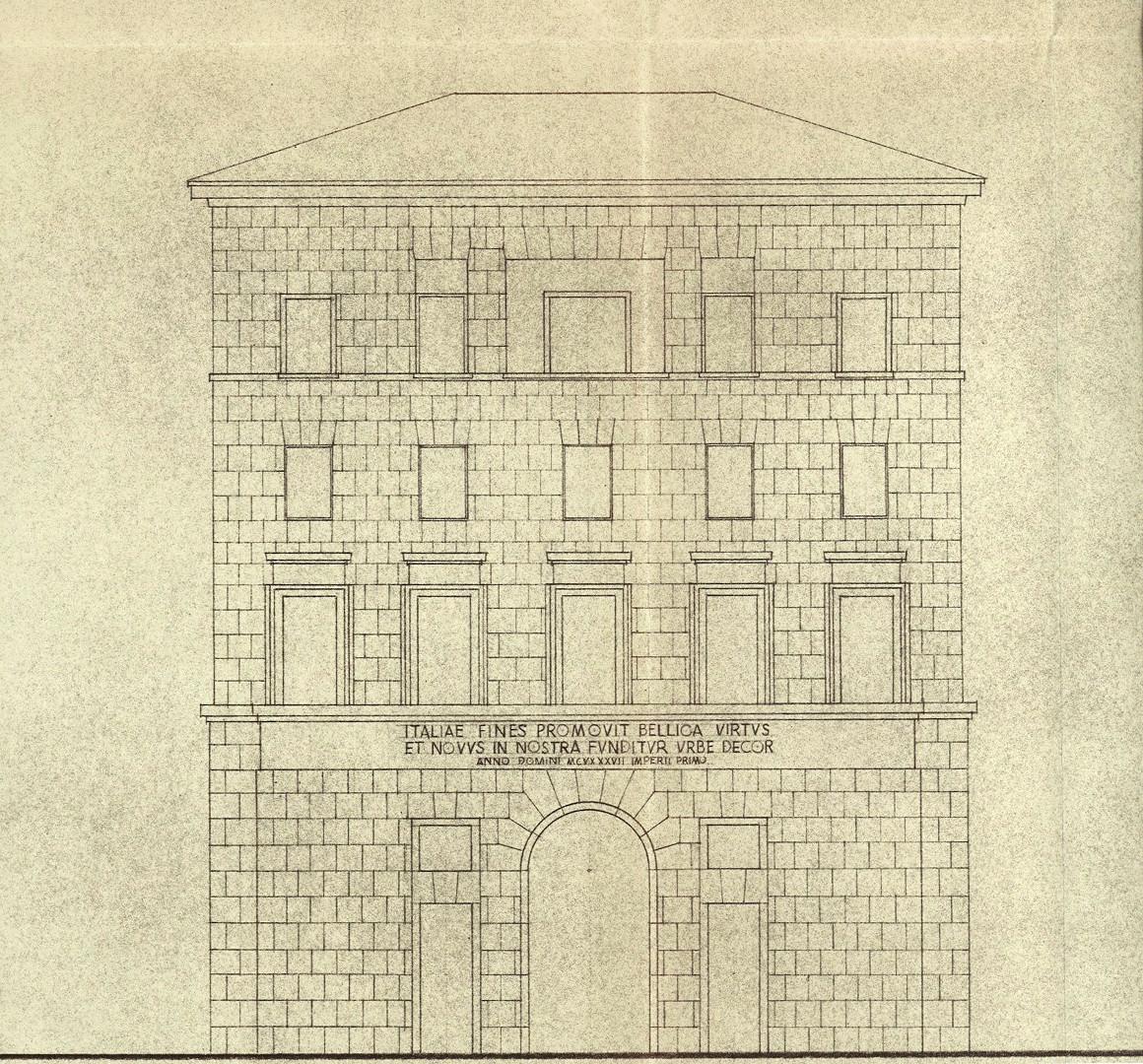

In a completely contrasting tone, in full Fascist style, adorning the front of the building facing Piazza Sant’Andrea della Valle, where Corso del Rinascimento starts, the inscription “compiled” by historian and poet Raffaello Santarelli reads:

Italiae fines promovit bellica virtus

et novus in nostra funditur urbe decor

(The virtue of war expands the borders of Italy

while a new beauty takes shape in our city, transl.)

where the first verse of the elegiac couple, with the caesura bellica virtus, exalts the recent colonial victories, and the second refers to the new Rome envisioned by Mussolini, for whose novus decor INA provided a significant contribution, participating in the realisation of a new road, Corso del Rinascimento, and the renovation of Via della Conciliazione.